OK, let's recap. In my

first post on color, I concluded that the standard three-primary color wheel is not useful for learning about using and mixing color. In the

second post, I briefly reviewed the Munsell color system as a means for describing color and for identifying visual compliments. In the

third post, I talked about the difficulty of developing a simple system that could adequately provide a method for artists to mix color.

What we're left with is coming up with color-mixing strategies that can allow a painter to get the job done without too much frustration. Unfortunately, this is complicated stuff, with lots of exceptions and special considerations. It doesn’t make as neat and easily-explained an idea as a simple color wheel. There’s just kind of a lot of stuff that’s important (or at least useful) to know about. And because all of the stuff interrelates, it’s hard to split it up into easily-digestible topics. But that’s what I’ll try to do. In this post, I’ll discuss value. Later, I’ll talk about controlling hue and chroma. Of course, since they are so closely interrelated, in each discussion of one of the three components I’ll also have to talk about the other two.

GETTING THE VALUE RIGHTIf you’re having trouble mixing a color with exactly the right hue, chroma, and value, concentrate on at least getting the value right. The brain weighs value far more strongly than it does hue and chroma. There are any number of paintings out there with wierd hues and no consistent use of chroma, but they work because the values work. (That’s not to say that hue and chroma aren’t important—they are—but to emphasize that value is the most important of the three for a beginning or intermediate painter to concentrate on.)

Value should be considered at two levels in realist painting. First, you need to consider the value structure of the painting as a whole. Do you want most of the painting to be light (a high key painting), most of it to be dark (a low key painting), or for there to be some kind of balance across a wide value rang (a full key painting). What is the range from darkest dark to lightest light? It’s useful to establish that range early, because every object will be rendered in relation to that key.

Overall Value RangeAs you think about this, you need to be aware that the value range of paint has only a small portion of the value range of human vision. Consider a painting of a sunset. That sun is much, much brighter than your highest-value white (which you’ll need to tone down in order to get the right hue and chroma). In order to give an impression of that brightness, you will need to make the rest of the scene quite a bit darker than you otherwise might. You are choosing a value scheme that represents the value relationships most important to the composition. That means that you won’t be able to have much contrast in the darks, because their value range is compressed in order to emphasize that very strong light.

On the dark side as well, the blackest black on your palette reflects a lot more light than a really dark shadow does. So there are times when you need to compress the lights in order to show a full range of contrasts in the shadows. Of the painting media, by the way, oil paint has the widest value range, particularly in terms of really dark darks. So it's easier to create believable three-dimensional form with oil paint, and that's one reason why it's so popular.

Therefore, in making decisions about the key of a painting, you need to accept that you are necessarily working with a limited value range, and you need to make intelligent choices about how you use it. There is no such thing as “paint what you see” in this calculation. Artists often manipulate the value range to achieve a specific effect. Rembrandt and Carravagio, for example, both painted low key paintings. But more than that, they made the darks very, very dark, the midtones quite dark, and the lights very light. That creates a marvelous dramatic effect, but there’s nothing realistic about it. It is worth looking at a lot of paintings and thinking about what choices the artists made regarding value range, because those are the same choices youre going to have to make every time you paint. Trying to go for a middle road, in which the lights are fairly light, the midtones are fairly medium, and the darks are fairly dark, is not always the best choice, because it isn’t very interesting and because it’s often not the right way to represent the emotional content of the scene. Don’t think that hue and chroma are the primary determinents of the way your painting feels, because often the real money is where the value is.

Light and ShadowWithin the overall value scheme of your painting, you’ll need to consider value as you work on each object or passage. Often, it’s good to think in terms of two, three, or (maximum) four values in the mass areas each object depicted. On the Munsell value scale from 0 to 10, for example, you might paint the shadow side of a house at value 3 and the light side at value 4. A head might be represented at value 5.5 in the upper lights, value 5 in the darker lights (sometimes called the “halftones”), value 3.5 around the terminator (the shadow edge), and value 4.5 in the reflected lights. You could mix these tones on your palette before you start, lay them down in the appropriate areas, then blend as desired. You could then add highlights at value 6.5 and dark accents at value 3. Doing it in such a pre-planned way can be much easier than figuring it out as you go.

To get these values right, it’s much easier to think about relationships than it is to think about matching the actual value of the object you’re trying to paint. So if the overall key of your painting sets the value of the light side of a cube at value 7, the thing to do is to observe and think about how much darker the shadow side of that cube is. What value in paint best reflects the value relationship you are observing in real life? Is it a 5? 4.5? It takes a lot of practice to get these kinds of relationships right across an object, and then to keep those relationships right across many objects in a single painting (many beginner paintings seem to be keyed differently in different parts of the picture).

One useful exercise is to do a series of paintings in a single hue. If you do it in shades of grey, it is called a grissaile (pronounced gree-zai). A 50/50 mixture of black and raw umber is a good base tone for a grissaile that you can mix with different amounts of white to get the desired value. Doing a series of grissaile studies can help develop your ability to judge and paint value. For each stroke of paint you put down, think about whether it should be darker or lighter than the paint surrounding it, and by how much. Over time, you’ll achieve a much greater sensitivity to value.

One of the typical mistakes that beginners make is to focus on hue and chroma at the expense of value. They might be trying to paint a figure, for example, and mix up some “flesh tone” (or they might have a tube labelled “flesh”). They proceed to paint the whole figure that color, then timidly throw in a slightly darker tone for shadows and edges. The figure looks flat and unconvincing. If you are going to concentrate on a particular subject, and you want it to look dimensional, you need a fairly wide value range within that subject. If that means compressing the lights or darks so that background elements have less contrast, that’s OK. If you’re painting a figure, the shadows on that figure should be a significantly darker than the lights. It is only with a wide dynamic range that you can create the illusion of three dimensional form. I remember when I was first taking painting classes, my teacher would look at my figures, sit down with my palette, and make the darks a good two value steps darker than I had made them (and I thought they were pretty dark). It was a painful experience, but it showed me how to create a successful illusion of form.

White and BlackSo how do you make paint darker or lighter? You can, of course, simply add black to darken and white to lighten. If you’re only concerned with value, that will always work. But both of those colors will, under many circumstances, distort hue and chroma.

White, of course, is a critical mixing color; it is the dominant pigment in many paintings. As you add white, however, the color tends to drop in chroma and will often shift hue. Hue shifting isn't too hard to deal with; you can add a touch of a warm or cool color (usually warm) to correct the hue. Dulled chroma is harder to fix (that's one reason why white paint isn't used in traditional watercolor technique). One strategy is to avoid titanium white when you don’t need a really bright opaque white. Both flake white and zinc white are less overpowering and have less tendency to kill the chroma in mixing. Zinc, especially, is good for this purpose. Another strategy is to use glazing, rather than mixing, to adjust hue and chroma. But it is the case that some high-chroma colors are very hard to approximate with paint. So when you are deciding on a value scheme for your painting, one important consideration is whether you will need to showcase any very high chroma colors. If that is the case, you may need to adjust the key of the painting so that those intense colors are the right value without having to lighten or darken them much. So, for example, you might use a higher-chroma, slightly less bright light and it will read as very bright in contrast to the relatively darker, duller colors elsewhere.

I think of black as being one of the less important colors on my palette. Some painters never use it, claiming that is is a deadening color, that there is no black in nature, and that excessive use of it makes your painting look like it has a hole in it. That’s hogwash. Take a look at paintings by guys like Leonardo da Vinci, Diego Velazquez, or Carravagio. They relied heavily on black. Can you really say that their paintings would have been vastly better if they had only known that some modern painters think black makes a painting look damaged? “That Leonardo guy, if only he’d known to avoid black, he might have made a name for himself!” Yeah, right. And don't think they didn't know how to darken colors without black, because they certainly did. They chose to use black because it was the color that worked best for what they were trying to accomplish.

That being said, it is certainly true that mixing a color with black will reduce chroma, and that black is best used with care. Sometimes, strong chroma reduction is exactly the effect you are looking for, so that’s when to use black. Black also causes color shifts. Mix black with a bright yellow (such as cadmium yellow light). Do you get dark yellow? No, you get an olive green (which can be quite useful). Under many circumstances, black acts like a very, very dark blue. Black is often best used the way it was usually used in the 15th century, to darken (and reduce the chroma of) earth colors and other low-chroma colors. I don’t usually use black as a dark dark; instead I tend to make a really dark mixture (such as ultramarine and burnt sienna or viridian and pyrol ruby) and use that. In part, that’s because in oil paint pure black takes a long time to dry and is a relatively “fat” color. But it’s also because pure black is a bit dead compared to mixtures.

Controlling ValueSo, if we need to be careful with white for lightening and if black is of limited use in making colors darker, how do we manage value? Carefully.

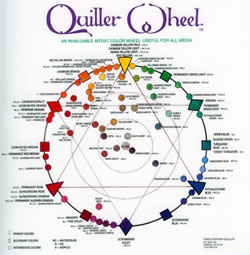

Take a look at a color wheel, particularly the colors on the outside of the wheel (the highest chroma pigments in each hue). You’ll notice that warm colors. like yellow, are quite high in value. By contrast, cool colors like purple are relatively dark. So your value mixing strategy will need to depend, to some degree, on what part of the color wheel you’re working with.

For example, how do you make a dark yellow? Do you look on the other side of the color wheel, find that a violet is the compliment of yellow, and mix that in? That doesn’t work very well, because many warm colors don’t have a true mixing compliment (they don’t mix to a neutral grey). So violet added to yellow produces a severe color shift away from the yellow hue. Fortunately, there are dark yellows already available—browns are basically dark yellows. So, as artists have been doing for many centuries, you don’t try to mix a dark yellow. If you want to depict a gradation from a light yellow to a dark yellow, you blend in a series of brown colors: cadmium yellow to yellow ochre to raw sienna to burnt umber, for example. Of course, if you don’t like earth colors, it’s perfectly possible to mix similar ones. Some artists like to use a very limited palette of only cyan, magenta, and yellow; with those and white, you can mix colors very similar to yellow ochre, raw sienna, and burnt umber. Personally, I find it much easier to simply use the earths.

How do you make a dark purple? Easy. Purple pigments are already dark, so all you have to do is adjust the chroma (if needed). If you need it even darker, you can mix it with dark transparent colors that are near to it on the color wheel (a transparent dark blue like Prussian blue and a transparent dark red like pyrol ruby, for example). You could even add a touch of black. How do you make a light purple? You’re probably going to have to use some white. If you need a light, high-chroma purple, you may have some trouble, because the white is going to knock the chroma down. So you may need to start with the highest-chroma purple you can find (such as dioxazine violet), so the final result remains relatively chromatic. As noted earlier, you might also want to use zinc, or a zinc-flake mix (a big glob of zinc by itself dries a bit brittle and that can affect the stability of the paint film). If you need a light, low-chroma purple, on the other hand, then mixing with white, then making slight adjustments to hue by mixing in small amounts of other colors, will probably work just fine.

It is also the case that, for many cooler colors like blues and violets, mixing with a small amount of white will increase the chroma. For example, in oil paint, ultramarine blue with a bit of white added is more chromatic than plain ultramarine. But adding a lot of white decreases the chroma. Warmer colors are tend to be at their maximum chroma straight out of the tube.

The easiest overall mixing situation is when you are trying to reduce chroma at the same time you are adjusting value. If the color has a mixing compliment, then, typically, that color will reduce value and chroma at the same time.

Mix the Value FirstWhen mixing two colors, it’s often a good strategy to first get both of those colors to the intended final value. Then, when you mix them together, it’s much easier to judge hue and chroma. If you have a clear idea of what colors you’ll be working with in a painting session, it can be useful to mix up a series of paint strings. One string is a single hue/chroma along a series of values. So, for example, a useful flesh tone is a neutral mixture of cadmium green and cadmium red. You might create that neutral brownish color on your palette, then mix in different amounts of white to make a series of gradations from very light brown to the base cad green/cad red mixture. You could then make darker tones along the same string by adding different amounts of raw umber. Now you have a string of one hue and chroma, but different values. Another string might be based on yellow ochre as a base tone, mixed with different amounts of white to make lighter tones and different amounts of raw sienna and burnt umber for darker tones. As you paint, if you need a hue that is in between the two strings, it’s easy to mix paint from each string at the same value to get the right hue.

Working with a set of pre-mixed values is called a set palette. Some artists take it to extremes, always mixing up a pre-set group of value strings before staring to paint. If you do this habitually, it helps to mix a lot of each paint value in advance and put them into tubes—that way, you don’t spend half of each painting session mixing strings of paint. I don’t do that, but I do typically mix two or three strings at the beginning of a painting session and work from them. You can buy sets of pre-mixed neutral greys at different values from several companies; the

greyscale set from Studio Products even comes graded according to Munsell values. I’ll come back to the usefulness of neutral greys later on when I talk about managing chroma.