30 September 2006

Sorry for the low frequency of posts lately

I'd like to note that I've had more than 2,000 visits since I started the blog at the end of June. That's not much for sites like boing boing, which probably has more hits than that in a typical hour, but it seems pretty good for a personal site that restricts itself to a fairly obscure topic. Thanks for stopping by, and please feel free to leave comments.

I'll try to get back into the swing of things this week.

29 September 2006

Bottle of oil and blue glass

Awhile ago I posted on a little sheet of copper I had prepared for painting on. Here's what's on it now. Oil on copper, 5 x 7". It's not done yet—I need to correct a couple of elipses and clarify some of the details. But so far I like it.

The copper takes oil paint like nothing else I've worked on. Normally, any surface is either absorbent or slick. Either way, the initial application of oil paint can be a bit of struggle. Not copper. The paint flows right off the brush, with no streakiness, chattering, staining, or other problems. Also, you can incorporate the tone of the copper itself into the painting. I need to find a source for bigger sheets of thin copper to paint on.

24 September 2006

Renaissance layering

By layering, I mean variations on glazing. I am using that term broadly to mean any application of two or more layers in which the layers beneath contribute to the final visual effect. Glazing can be done with relatively transparent colors such as red lake, or with opaque colors such as vermillion (if it is applied thinly enough). In both the Netherlandish and Italian traditions, glazing was critical to the final appearance of important parts of almost all paintings, but the way they used glazing was different.

In Netherlandish painting, glazing was used to adjust values with minimal loss of chroma. Typically, an opaque color, such as vermillion, was applied first. The initial layer was typically flat—i.e., with no attempt to model the forms. Then a transparent pigment of similar hue, such as red lake, was applied over the initial flat layer. The transparent color was applied thinly in light areas and thickly in dark areas. Often multiple layers were applied to darks. Because thicker layers of transparent pigments absorb more light than thin layers, a thick layer is darker than a thin layer. This approach to modeling, in which darks are created not with darker colors, but with thicker, light-absorbing layers, creates an optical effect that is completely different than simply mixing a light, a midtone, a dark, and then blending them. Blacks and other dark, dull colors were avoided in Netherlandish glazing. Fully-modeled objects have a jewel-like tonality that jumps off the picture. This glazing technique wasn't used throughout the painting, but was carefully applied in order to control the structure of the composition. It was not used in modeling flesh tones, which were typically done very thinly, in one or two layers.

In Italian painting, by contrast, glazing is used to generate hues through optical mixing of layers. For example, in early Renaissance Italian tempera painting, flesh tones are created by first applying a layer of dull green, then modeling in a dark dull brownish green. On top of that, the flesh color is created by applying an opaque pink (flake white mixed with vermillion) thinly enough that the underpainting shows through. Later in the Renaissance, when Netherlandish oil paintings began to be imported, the Italians tried to copy those effects in oil paint. But while they knew how to make oil paint, they didn't know about Netherlandish layering. They created darks by mixing dark dull colors, including black. Italian oil paintings from that period show none of the chroma intensity in the darks that make Netherlandish paintings so special. It wasn't that they were stupid; it was that they thought about color and layering in a different way, and that approach created a different set of effects. The Italian method was also useful. Botticelli, for example, underpainted foliage with black before glazing over with greens. This makes the foliage fade into the background. He underpainted flesh with yellow ochre, to make flesh tones that had a warm cast. Michelangelo used a traditional (and then somewhat old-fashioned) underpainting with greeen earths for flesh tones. If he wanted two different tones of blue drapery in a painting, he would underpaint one with black, then ultramarine mixed with varying amounts of white and black. The other would be done in the same set of ultramarine gradations over white gesso, creating two completely different ranges of blue with the same surface pigment. Leonardo's sfumato method involved a very dark underpainting in dull earth tones, followed by glazing with light colors mixed with a lot of white. Italian painting is generally brighter and more chromatic than Netherlandish painting, but the darks are more dull. The eye picks up on these differences very easily.

It's useful to understand how both of these kinds of layering effects are accomplished, because if you know how to do both, you have a broad range of useful tricks.

23 September 2006

20 September 2006

How to get oil paint to dry quickly

Some painters are fine with letting paintings dry for days or even weeks. They work on more than one piece at a time and come back to each one when it's ready. But sometimes you want stay with one piece, working every day. Here are some ways to control the rate at which oil paintings dry:

1. Paint in thin layers (like the thickness of a normal coat of house paint).

2. Avoid slow-drying pigments like titanium white and ivory black. Use fast-drying pigments like lead white and burnt umber.

3. Avoid paints made with slow-drying oils like safflower and poppy. Also avoid walnut oil, which dries faster than safflower or poppy, but slower than linseed.

4. Use a lean lead-containing medium such as Maroger's.

5. Add a bit of turps to the first layer. Turps doesn't make paint dry faster, but it makes the paint layer thinner, which does make paint dry faster. Don't add so much turps to paint that it becomes washy or watery. Just add a little bit.

6. Paint on a panel primed with glue-chalk gesso. The first layer will have some oil absorbed by the gesso, so the paint dries more quickly.

7. Add small amounts of metallic driers to the paint. I prefer lead napthenate. I add one tiny drop (from a toothpick) per blob of paint on the palette and mix thoroughly. Excessive use of driers will damage the paint film, but that much should not be any problem. I generally add driers only to slow-drying pigments.

Some painters also use alkyd mediums such as Liquin, Neo-Meglip, and Galkyd. I don't use alkyd mediums and I don't recommend them. However, they do make oil paint dry faster.

When I need to, I can get oil paint dry in a day, so I don't usually have to wait for a layer to dry before I can paint over it. Sometimes, I choose to use a medium that makes the paint dry more slowly, or I use a slow-drying pigment like titanium white. But when I do that, I know that the paint will need extra time to dry. My glazing medium (a 50/50 mixture of black oil and Venice turpentine) is somewhat slow-drying, so glazes usually take two or three days to dry.

It's also the case that I often complete one section of a painting at a time. That way, it doesn't matter whether yesterday's paint is dry, because today I'm working on a different part of the picture.

16 September 2006

Online workshop: Renaissance Italian painting

14 September 2006

Jacob Collins

You can see his work at his web site. There's some other good stuff at the Art Renewal Center.

I hope he doesn't mind my posting a sample of his work:

Pigments, paints, and color mixing wheels

I know that you've all been waiting with great anticipation for this next post in the series, in which I reveal a simple and comprehensive method that allows you to easily mix exactly the color you want with just a few inexpensive tubes of paint. Alas, I must now confess to you that—so far as I know—such a system doesn't exist. What I can do is to describe some of the issues involved in the complex subject of color mixing and then present several ways to approach the problem.

First, let’s talk a little about paint and pigments. Pigments are colored powders. Some of them are rocks and dirt that have been ground up and purified, some are simple chemical compounds, some are created via complex modern organic chemistry, and some are tiny water-soluble particles that are made suitable for painting by attaching them to larger uncolored particles. Each pigment has a characteristic color (hue, chroma, value) which is the result of the pigment particles absorbing some wavelengths of light and reflecting others. Changing the particle size often changes the color, sometimes radically. Heating many pigments will change the color—burnt sienna is just a cooked version of raw sienna. Changing the medium in which the particle is suspended often changes the color due to a different refraction index—ultramarine blue is much darker in oil paint than in egg tempera. Some pigments come from a single pigment company and in that case all paint makers start with the same raw material. Other pigments are available from multiple suppliers and each may provide a version that is subtly, or not so subtly, different—there are many, many variations on cadmium red. The color of most pigments is different when they are laid on thick (this is called the masstone) and when they are laid on in a thin layer (this is called the undertone). Pigments are usually described as “opaque,” “semi-transparent,” or “transparent.” That refers to how well light passes through the pigment when it is mixed into a transparent binding vehicle. Transparent pigments are much darker and lower in chroma when they are thickly applied than when they are thinly applied. Pthalo blue is a very bright color when spread thinly, but a dark, almost black, blue when it is very thick. Opaque colors are more likely to have a masstone and undertone that are basically the same, although there are exceptions. Transparency varies somewhat from one painting medium to another, because it is a function of the refractive indexes of the pigment and the binding vehicle. With water media, the refractive index of the vehicle changes as it dries, so what looks transparent when you lay it on may be fairly opaque when the paint dries.

Almost no pigments are manufactured for artist’s use; they are made for large-scale industrial purposes, such as signs, cars, house paint, printing, cosmetics, and all of the other industries that use these materials in far greater quantities than artists do. Paint manufacturers buy these pigments and grind them with a binding vehicle and other components to make paint. (In some cases, individual painters may purchase powdered pigments and make their own paint.) A tube of paint may contain only one pigment or several; if adulterating pigments are present in small amounts, it may be considered legitimate not to note that on the packaging. Many paints are mixtures of pigments to make a certain color not obtainable with just one pigment—many companies sell a paint mixture they call “flesh,” for example (usually this means some sort of pinkish attempt at caucasian skin tones). Some companies sell mixtures that are designed to mimic an expensive pigment. So a paint called “cadmium red hue” won’t contain any of the expensive cadmium red pigment, but instead will have a combination of other pigments designed to have similar color characteristics.

So, given these issues, it’s impossible to just develop a simple model of color mixing; every artist uses different pigments, in different media, made differently by each company (and, perhaps, formulated differently from one batch to another). And every artist applies paint differently.

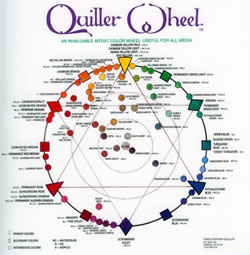

Even if you could correct for all of these factors, there are other challenges. Let’s look at one attempt to produce a color mixing system for artists: the Quiller wheel. Stephen Quiller, a working artist (mostly in watercolor and acrylic) has designed a color wheel to assist artists in figuring out how to mix color. A large number of common colors are placed in various positions around the wheel. Where the color is placed depends on (1) the color’s hue and chroma; and (2) the color’s mixing complement (which is directly across on the other side of the wheel). Color placements are a matter of Mr. Quller’s judgment and extensive mixing experience, not any sort of mechanical measurement. Lower chroma colors are closer to the center of the wheel, while higher chroma colors are closer to the outside. So if you are using the Quiller wheel, and you want to mix a particular color, you would find the location on the wheel of the color you want to mix, then mentally draw a straight line between two actual colors. In theory, any color on that line can be mixed with those two colors. You can therefore find a mixture that is the one you want.

A color mixing wheel such as this will often get you into the right ball park when mixing colors. Unfortunately, it has some problems. First, there are the issues of paint variability discussed above. One cadmium red light is not necessarily the same as another. Second, there is the problem of hue shifts. Because of the physical properties of pigment, when two colors of paint are mixed in different proportions, the hue doesn’t always follow a straight line that can be plotted on a wheel. The hue instead follows a curved path that is not predictable just from knowing the colors of the two paints being mixed. This curved path might mean that the color you want cannot be mixed from the two colors you’ve selected, even though it looks like that should be possible from looking at the color wheel. Another problem with a mixing color wheel is this: paints can have multiple mixing compliments. A complimentary mixing pair, you will recall, is two paints that, in some ratio, can be mixed to form a grey color with 0 chroma (or very, very close to 0). A mixing color wheel attempts to place complimentary pairs directly opposite each other on the wheel. But because in real life a pigment may have more than one mixing compliment, its actual location on the wheel is an arbitrary choice. Since the wheel is trying to do two things that are not always compatible (show the appropriate location for mixing and show complimentary pairs), it represents a compromise. It's a set of guesses designed to help the artist get close to what he or she is looking for. It’s not a scientific instrument; it’s a compendium of rules of thumb, and those rules of thumb are often wrong. Another problem is that the wheel shows purples and yellows at opposite sides of the wheel, indicating that they are complimentary mixing pairs. But the reality is that most yellows and most purples don't have a mixing compliment, so the wheel deceives you when you try to mix those colors together.

There’s another problem with mixing wheels. They help you get into the right ballpark with the hue you are looking for. They can also give you an idea of what chroma any given mixture will be, since you should be able to find the approximate chroma of a mixture by finding where it lies on a line between two mixing pairs; the closer to the center of the circle, the lower the chroma. But what if you mix the perfect hue, and it’s the right color. How do you get the value you want? If you want a darker color, mixing with black will reduce the chroma drastically and will often shift the hue. If you want a lighter color, mixing with white will also reduce the chroma and will often shift the hue as well. So you may have the perfect mixture, except for value, and still not know how to get the final color you want. The color mixing wheel doesn’t get you to the finish line.

That all being said, the Quiller wheel (or something like it) is a useful tool that can be helpful, especially for beginners, in figuring out the basics of color mixing. There are other mixing wheels out there, sometimes with fancy sliders that you can turn around a cardboard wheel. There is also color mixing software that attempts to do the same thing. They all have significant limitations when it comes to making subtle mixtures of actual paints.

So what’s a poor painter to do?

Well, since many real-world painters manage to get good results with color, it is obviously possible to do so. In the next post, I’ll discuss several strategies for color mixing.

13 September 2006

11 September 2006

Politics

Since this is a web log, I'd also like to note that I have strong opinions about politics, international relations, history, economics, the nature of freedom, the proper role of government, and other such matters. And I'm not going to say anything about those topics on this site. Please feel free to imagine, if it matters to you, that my beliefs and yours are remarkably similar.

08 September 2006

I'm having trouble getting Technorati to register that I still post to this blog. According to them, I haven't posted here in weeks. The link above is my attempt to correct this by deleting this web log from their list, then re-register it. The process includes posting the link above. It doesn't seem to have worked. I've followed the instructions on how to do this, and they used to register my posts. Then they just stopped. Anyone have a suggestion?

07 September 2006

More on color

In my last post about color, I discussed the inadequacies of the standard color wheel and explained why we're going to have to replace it with two things: (1) a more accurate way to describe color; and (2) a system for approximating real-world paint mixing. In this post, I'll talk about describing color. As I do so, I'll refer you to certain sections of the Handprint web site (from which I have stolen shamelessly) in case you want more detail.

Although we often still see the standard three-primary color wheel in books about painting and color mixing, it really went out of date in the late 19th century, when guys like Ogden Rood demonstrated that it pretty much stinks for describing color accurately. There is nothing in the way humans perceive light to support the idea of three unmixable primary colors (red, yellow, blue), each of which is complimentary to a specific mixable secondary color (red and green, yellow and violet, blue and orange). In fact, it makes sense to me that there are no special primary colors at all, whether the traditional artist's primaries (red, yellow, blue), the printer's primaries (cyan, magenta, yellow), or anything else.

A number of more accurate ways of describing color have been developed. Many of them are designed primarily to support the needs of the print industry, the dye industry, manufacturers of video equipment, and other commercial ventures. They are needlessly complex for our purposes. The best system that is comprehensive enough, but not too complex to be easily understood, is the Munsell color system. It was first developed in the early part of the 20th century and has been updated a few times since then, although the original structure remains. Any such system represents a series of compromises, so there are ways in which Munsell is imperfect, but overall it suits our purposes better than any other that I am aware of.

Rather than a color wheel, Munsell is built around a three-dimensional color space. This space takes the shape of an irregular cylinder. Munsell uses three properties of color: hue, chroma, and value. I described those properties in detail in a previous post.

Running up the center axis of the cylinder is the property of value. At the bottom of the cylinder is value 0 (pure black); at the top is value 10 (pure white). So, for example, a value 6.5 gray is fairly light, while a value 1.0 gray is almost black.

Running around the outside of the cylinder is a hue circle. It is defined by five principal colors (there are no primaries in Munsell). These colors are red (R), yellow (Y), green (G), blue (B), and purple (P). These are generally represented in clockwise order, starting with yellow at the top. The five principle hues have five intermediate hues in between them: yellow red (YR), green yellow (GY), blue green (BG), purple blue (PB), and red purple (RP). Within each of the hues are ten subdivisions, with 5 at the center. So 5BG is a pure blue green, while 2BG is more blue and 9.3BG is more green.

Each of the principal hues has a visual compliment that is the intermediate hue directly across from it on the circle. So the compliment of red is blue green, the compliment of yellow is purple blue, the compliment of green is red purple, the compliment of blue is yellow red, and the compliment of purple is green yellow. These compliments correspond (approximately) to how humans see color. Munsell compliments are reasonably close to actual data on afterimages. If you stare at a spot of green for a long time, and then look at a neutral gray surface, most people who are not color blind report that they see an afterimage within Munsell's red purple range. The same goes for each of the other complimentary pairs on the hue circle. You see these afterimages because of the way that cone cells on the retina work. I'm not going to describe the physiology, but it helps to know that these are real phenomena (which I am oversimplifying drastically here), not arbitrary or aesthetic conventions.

If the value parameter is a line down the center of the cylinder, then the chroma parameter radiates outward from that center line to the edges of the cylinder. Zero chroma (gray/black/white) is at the center. Moving outward are increasingly chromatic (intense) colors. So a value 6 yellow at chroma 1.5 is basically a warm grey (not very chromatic), while a value 6 yellow at chroma 15 is very intense.There is no arbitrary maximum chroma, so the chroma scale for each hue runs from 0 to however intense that hue can get. As new, brighter pigments are developed, they are simply placed at higher chroma levels than those of older pigments. Any pigment can therefore be placed upon the Munsell color tree. Because of the physics of light and the nature of color vision, the maximum possible chroma is different for different hues. For example, the maximum possible chroma of a light-valued yellow is much higher than that of a light-valued purple. Maximum chroma for a given hue is also different depending on value. So the Munsell color space is a bumpy, uneven cylinder (when Munsell first invented this system, his realization that the color space couldn't be symetrical was a big improvement over previous systems that had tried to cram a messy reality into an idealized circle or triangle).

Colors are named in Munsell in the standard notation of hue value/chroma. So vermillion is noted as 8.5R 5.5/12. That means that, within the hue of red, it is at position 8.5 (closer to yellow red than a pure red), with a value of 5.5 (right in the middle) and a chroma of 12 (fairly intense). Some paint manufacturers, such as Liquitex, put these numbers on every tube of paint. Unfortunately, that's rare.

The Munsell system has been updated several times to make it more technically accurate, but none of those updates is significant for our purposes. You can buy color sets from the Munsell company. They consist of a book describing the system, a bunch of color chips (sets have either glossy chips or matte chips), and pages with little pockets that the color chips fit into. The idea is that you learn the system by fitting each chip into its appropriate pocket. I haven't bought a color study set, not because I'm uninterested but because they cost hundreds of dollars. Getting a set and placing all of the chips would not be a waste of time for a serious student of painting.

That's Munsell. Boy, that was a lot of explanation, even though I picked the simplest useful color system that I know of and avoided extraneous detail. Color is really complicated.So how is Munsell more useful to a painter than the old three-primary color wheel? First, it dispenses with the confusing idea of primaries and secondaries while more accurately identifying useful complimentary color relationships. These relationships are of great value in choosing harmonious color relationships. Second, as you become more familiar with Munsell, you can begin to think about colors in terms of how they relate to each other within the color space. If you are looking at a blue wall, for example, and you are thinking in Munsell terms, you can figure out where the color lies and how to accurately describe it. What is its hue? How chromatic is it? What value is it? How do those parameters compare to other colors you are trying to work with? How do the hue, chroma, and value of the wall relate to the hue, chroma, and value of the blob of paint you are trying to use to represent it? Some artists pre-mix a set of colors on their palette in Munsell value steps. Several companies sell paints that are graded according to Munsell; Studio products sells a set of neutral grays and another set of greens, all the same hue and chroma, of different Munsell values. These are particularly useful for underpainting.

There isn't much in Munsell that helps you figure out what color you will get if you mix two paints together—that's not what it's for. What it does do is help you decide what color you are trying to get to. And for that, its really excellent.

Lots more on color in future posts.

05 September 2006

Update on Robert Doak

I wrote about Robert Doak's oil paints back in July, when I first started this web log. Today, he called me. He had noticed my post here, looked up my phone number on his customer list, and wanted to thank me for recommending his products. He also asked about my statement that some of his paints separate, so that a oil oozes out of the tube when you remove the cap (I've only had this happen with a small percentage of his paint tubes).

He said that he almost never gets this complaint. He wanted me to know that, when it happens, it does so because he uses very little stearate, which is a clear, inexpensive pigment that paint manufacturers use to prevent separation. It also reduces pigment load and (when used in excess) makes paints more thick and difficult to work with. Cheaper brands of oil paint use a lot of stearate, to improve shelf life and reduce the percentage of expensive pigments in their paint (that's part of why student grade paint is usually very stiff). I have never been concerned about separation with Doak's paint, because I know it happens because he emphasizes pigment load and smooth handling over shelf life.

In the original post I said that the way to deal with separation was to squeeze your paint out onto absorbent paper, wait a couple of minutes, then transfer the paint to your palette with a knife. Mr. Doak said doing that over and over might tend to leech the oil out of the paint tube and cause the paint in the tube to harden (I haven't had that happen). He recommended instead storing any tube of paint with separation issues cap downward, so the oil moves back up through the pigment in the tube. I told him I'd try that and pass on the tip.

I still strongly recommend his paint.

Tags: painting, oil painting, painting materials

Miles Mathis

At his web site, he has a number of essays that express strong, independent opinions about art and culture. He writes well and with great conviction. I certainly don't agree with everything he says, but I find it very worthwhile to check his site from time to time and see if he’s written anything new. What he writes is almost always worth reading and thinking about. He recently posted a short essay on his painting materials and techniques. He’s a traditionalist and—not surprisingly—he's cranky about how most other artists are lazy with choosing their methods and materials. He paints on linen and primes it himself with lead white. He uses mostly an earth palette and believes strongly that those are the colors that can best be used to represent flesh (I often use earths for flesh tones also). He uses a home made dammar final varnish.

Many buyers have said that my paintings have the same sort of paint that old paintings seem to have, whereas contemporary paintings, even when they are very good, don't. There is a very simple reason for that. I work differently than most modern painters, and that difference starts with my canvas. In my opinion almost all modern materials are garbage, pure and simple. They were created for speed and convenience and price and safety, not for quality. Most professional artists know this and will admit it, and yet most professional artists, even at the top of the field, use inferior pre-stretched canvases.

While I agree with much of what he says, I do have a couple of quibbles. I, too, like to prime with lead, but he uses a lead white paint (Old Holland cremnitz white). I'd recommend an actual lead white primer (he may not be aware that those exist on the market), such as Studio Product's excellent white lead in black oil primer or Williamsburg's lead oil ground. He also confuses organic and inorganic pigments. Earth pigments are not organic; they're rocks and dirt. Many modern pigments, such as pthalocyanines, are classed as organic, since they are based on various carbon molecules. He does correctly label the cadmium colors he despises as inorganics. But the gist is clear: he prefers an old master palette (even if he doesn't know how to describe it technically) from before the explosion of modern pigment manufacture in the 1800's. Specifically, he says he likes Titian's palette, although he doesn't say exactly what he means by that. Titian used colors like azurite and lead tin yellow that are pretty hard to find these days (but not impossible). If you like writing that is passionate and interesting, take a look at his site.

04 September 2006

Can we talk about color?

Color theory, as found in most art books and art classes, doesn't actually help a working painter all that much. You may find that whenever you try to mix a specific color, you get "mud." You might cope by just getting a lot of tubes of paint so that you rarely have to do much mixing. Seeking clarity, you might buy a book like "Blue and Yellow Don't Make Green," which promises a new approach to color, but is based on concepts invented in the 1700's. (And written in an irritable, pretentious, finicky style. By a guy who doesn't know how to construct grammatical sentences. But I digress.) Or you find something like the Munsell color system, which does a good job describing color, but doesn't show how to mix those colors after you identify them. Reading books and looking around on the internet gets you a little closer, but mostly, by trial and error, you just figure out what works, using a small subset of available pigments. You memorize some useful mixing recipes. A lot of the time, you muck around with paint until you get something that looks about right.

If you delve more deeply, you find that the subject of color is incredibly complex, because it requires reconcilliation of the physics of light wth the messy, non-linear neuroanatomy of the human retina, optic nerves, and visual cortex. Most of what's written about color is not for painters, and most of what's written for painters is by people who've learned to mix paint, but don't actually understand color that well. One excellent resource is the very fine handprint web site, where the author has done incredible amounts of reading, research, and testing with watercolor paints. But the stuff he has on color goes on and on, and on and on, so it's hard to find the real practical stuff (it's there, and it's worth looking for).

So, while I don't pretend to have a really thorough understanding of color as it pertains to painting, I thought I'd try to boil down what I do think I have a clue about. It's a little easier for me, since when I was in graduate school I did a bunch of work with the psychology of visual perception (I'm even published in the field). I will not, however, subject you to complex equations, the details of opponent process color vision theory, or technical color space specifications that are designed to meet the needs of the print, computer monitor, and motion picture industries (you're welcome). I'll try to stick with what you need to know in order to describe and mix colors.

So, to start out, we need to dump the color wheel. It was a useful innovation back in Isaac Newton's time, but we've moved on since then. The biggest problem with it as a tool for painters is that it's trying to do two different things at the same time, and it does both of them poorly. First, it tries to provide a model of human color vision, including how the eye processes complimentary colors—whatever those are. But when you test how actual vision works, you find that the color wheel is a terrible model of color vision and that much more accurate models have existed for well over a century. Second, it tries to provide a guide to color mixing. It does that very badly as well, because real color mixtures don't fit the standard color wheel model in any coherent way.

It's become apparent to me that we must divide the topic of color for painters into two: (1) a way to describe color as it is found in the natural world and as the eye perceives it; and (2) a way to conceptualize how to mix desired colors using particular combinations of paints. There is no system that does both of those tasks, so let's just dispense with the color wheel and start over with two separate (albeit related) topics. And we'll get to those topics in later posts. I promise.

Three ways to use oil painting mediums

Here are three ways to use mediums:

1. An oily or resinous medium can be mixed directly with paint. If so, it is best to use the smallest amount that will achieve the effect you are looking for—generally no more than 20% of total paint volume, and preferrably much less. Use a knife to mix a bit of medium thoroughly into each blob of paint on your palette, or into whatever mixture you want to have the properties the medium imparts. Then paint normally. A good medium will make the paint handle more smoothly. Artists have various opinions about which mediums are best.

2. An oily or resinous medium can also be spread thinly onto the surface of the painting before applying paint (this is referred to as painting into a “couch” of medium). Wipe with a cloth or rub it in with the palm of your hand to get it as thin as you can. Don’t apply medium to areas where you will not be painting this session, since oil on the surface can eventually result in excessive yellowing. The couch method has the effect of lubricating the surface (which can make precise detail work easier) and reducing “chatter” (i.e., dragging and streaking of paint strokes). It also improves adhesion between layers, especially if the medium contains a balsam.

3. If you use a thin medium containing a high proportion of solvent, keep it in a small covered container next to you as you paint. Dip your brush in medium and mix it into the paint on your palette just before you apply it. Don’t make the paint watery; use just enough medium to make the paint more workable. Solvents can dissolve a lower layer of paint if you haven’t given it time to dry completely. Use solvents only if you have good ventilation and keep the medium container covered when you are not using it in order to limit evaporation.

Now go forth and smear colored goo on flat surfaces!

Tags: painting, oil painting, painting methods, painting mediums

30 August 2006

Rocks

Another photo from Ireland. In many places, walls like this are all over the place. I live in New England, so I'm used to countryside that has a lot of stone walls. But the number of walls in Ireland is simply amazing.

Another photo from Ireland. In many places, walls like this are all over the place. I live in New England, so I'm used to countryside that has a lot of stone walls. But the number of walls in Ireland is simply amazing.

Tags: photos, digital photography, Ireland

It's killing me

Kirsten is feeling better, though, and tonight I've worked out a deal with her to take care of Brendan while I paint for a couple of hours. I hope it works out that way.

Update: I got two solid hours on the latest in my "stuff hung on a nail on the wall" series. Ahhhhh...

28 August 2006

So you've decided to try oil painting

First, be realistic. Don't think you're going to make any masterpieces any time soon, and never think that there are any shortcuts. If you just want to play around and don't care about developing real skill, then just do that and have a good time. But if you are serious about learning to paint well, realize this: while it's not that difficult to learn how to make mediocre paintings that your mom will like (or tell you she likes), making good paintings is hard—really hard. It takes a lot of practice, regardless of talent, to learn how to paint well. You will make many bad paintings before you make your first good one. If you are someone who can't stand to be bad at something, over and over, before you get good, then oil painting isn't for you. Maybe you should try video games. You can find cheat codes for many of them that will make you invincible.

Second, keep it simple. It’s counter-productive to plan complicated projects until you have the skill to pull them off. Your subjects, to start off, should be simple. An egg, a mug, a tree. No people. No copying photos. Your goal, to start out, should be to do some bad paintings that no one will want to look at. If your goal is to make bad paintings, it won't be too hard to get there. After ten of those, you can start to think about paintings that are...less bad. You’ll learn more, in the same amount of time, by making several simple bad paintings than by making one complicated bad painting.

Third, there is no reason to start out by spending a lot of money or getting fancy with materials. Get a few tubes of decent, artist-grade paint. Don't get student grade, don't buy a beginner's painting set, and don't buy water miscibles or other convenience oil paints. A good starter palette would be titanium white, ultramarine blue, burnt sienna, raw sienna, and ivory black (you can get these from Robert Doak for well under $40—but don’t let him sell you anything else). Those pigments are all inexpensive and non-toxic (not that you should eat them). You won't be able to make bright, high chroma paintings with this simple palette, but that's a good thing: until you learn to mix neutral colors, a high chroma pallete would only force you to make luridly nasty paintings. Get some small primed canvases (no more than 8 x 10") or some of those primed canvas pads. Get some brushes—I'd suggest a couple of bristle flats about as wide as your thumb and some synthetic sable (soft) flats about as wide as your pinkie (if you have particularly wide or narrow fingers, adjust accordingly). Also get a pack of cheap plastic palette knives. Get a pad of disposable paper palettes and a big roll of paper towels. For cleaning brushes, either go to the hardware store and buy some odorless mineral spirits, or go to the art store and get some linseed oil. Get a basic easel—a cheap table easel will do. If you continue to paint, you'll be upgrading all of this stuff. If you find that you hate painting, find a niece or nephew to give the stuff to.

Fourth, learn to handle the paint. Set up your easel and a blank canvas. Squirt a little of each paint onto the edges of your palette. Make an abstract painting that doesn't look like anything. Play around. Until you get used to oil paint, you may find that it’s sticky and hard to manage. Don't thin your paint down to make it manageable; never add more than a tiny bit of oil or solvent to the paint. Learn how to load paint onto the brush; not too much, not too little. Learn how to make a flat area of one color that isn't streaky (hint: don’t be afraid to scrub the paint into the canvas with a bristle brush). Learn to make definite strokes; never dab it on. Mix two colors together with a palette knife—try ultramarine and raw sienna. That makes a gray. Add some white. That makes a light gray. Try mixing every combination of paints on your palette to see what colors they make. Learn how to make darks without using black (I’ve done many paintings in which the darkest darks were a mixture of ultramarine and burnt sienna). Black is a good mixing color, but it’s of limited utility for making other colors darker. When you make a mistake, learn how to scrape the paint off with a palette knife, wipe off the remainder with a rag soaked in a little bit of solvent, and start that section over. Learn to blend two colors, laying down two adjacent tones of paint, then using a soft dry brush (cleaned every few strokes) to feather between them, gradually developing a gradation. Use multiple brushes at a time—one for each color, or at least one for darks and another for lights. Learn how to apply light paint over dark paint (or dark over light, which is harder) without having them mix more than you want to and getting all muddy. This last skill takes a very light touch and plenty of practice.

Fifth, pick a simple subject and try to paint it. You may want to start with just a painting in one color, using just shades of black and white, or burnt sienna and white. Try a painting with just ultramarine, raw sienna, and white. You won’t be able to mix every color you see, but, in fact, you can’t do that no matter how many colors you use. Don’t drive yourself nuts with arbitrary limits, but try to make your first few paintings quickly, in an hour or two each. It doesn’t matter if they are any good, and if you are trying hard to make good paintings you’ll be too frustrated to continue. Your goal is to make some bad paintings that no one but you will ever see, learning from each one. Finish a painting, put it away without thinking about quality, and move on to the next one.

Sixth, after you’ve done ten or so small bad paintings, take a look at them. Are the last ones as bad as the first ones? What have you learned to do well? What is still embarassingly bad? What do you need to learn next? Understand that your own perception of your work will tend toward either absolute enchantment or utter loathing (often with rapid swings from one to the other). Learn to appraise your own work realistically. Try looking at it in a mirror—that sometimes helps. Find someone you trust to give you honest but not excessively critical feedback (but decide for yourself whether they are right or wrong).

Seventh, save up some more money and get some more supplies. You probably want some more colors. Add them to your palette one or two at a time after experimenting with how they mix with the other colors you already use. Try some zinc white, which is much less overpowering in mixtures than titanium. Try cadmium red or cadmium yellow. Learn about pigments and choose paints that are made with only one pigment (you don’t need paint companies to do your mixing for you). Get some more brushes. Think about a better easel. Think about better surfaces than acrylic primer. Think about making some panels. Think about more complicated subjects (but not too complicated). Look at good paintings by artists you admire and think about how they might be made. Are there any painting classes you could enroll in? Read the rest of this web log, other web sites, and books to learn more about what you can do with paint.

Good luck.

Tags: painting, oil painting, painting materials, painting methods

23 August 2006

Olden

The remains of a small medieval church on Inishmore, an island off the Western cost of Ireland.

The remains of a small medieval church on Inishmore, an island off the Western cost of Ireland.

Tags: photos, digital photos, Ireland

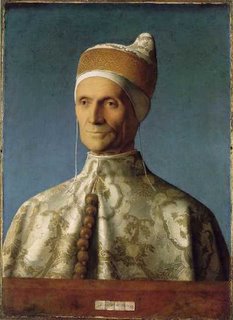

The most influential painter you've never heard of

The Venetian style became the primary style of oil painting, throughout Europe, for centuries; it encompasses a lot of oil painting even today. He is not the only one who contributed to the development of this style, but his were the core innovations. His students, Titian and Giorgione, continued to develop and expand on the ideas he had invented. It can be said that Rembrandt, Carravagio, Rubens, Velazquez, and pretty much every important painter up until the Impressionists, were painters in the Venetian style, developing and extrapolating on methods first introduced by Giovanni Bellini. And even impressionism could be said to be a logical extension and modification of the Venetian style using a more modern palette of colors. So it's definitely worth checking out his work.

The Venetian style became the primary style of oil painting, throughout Europe, for centuries; it encompasses a lot of oil painting even today. He is not the only one who contributed to the development of this style, but his were the core innovations. His students, Titian and Giorgione, continued to develop and expand on the ideas he had invented. It can be said that Rembrandt, Carravagio, Rubens, Velazquez, and pretty much every important painter up until the Impressionists, were painters in the Venetian style, developing and extrapolating on methods first introduced by Giovanni Bellini. And even impressionism could be said to be a logical extension and modification of the Venetian style using a more modern palette of colors. So it's definitely worth checking out his work.

Tags: painting, art history

20 August 2006

73% more convenient than regular oil paint!

Alkyds: These are paints made with a synthetic resin instead of a natural drying oil. The chief advantage to alkyds is that they dry overnight, and all colors dry at the same rate. The big disadvantage is that (to me) they smell awful. The handling is also inferior to the handling of high quality oil paint. Paintings done in alkyds should be labeled as alkyd paintings, not oil paintings.

There are also alkyd mediums, such as Liquin, Galkyd, and Neo-Meglip, intended to be mixed with regular oil paints. That's not what I'm talking about here.

Water miscible oil paints: These are oil paints made with a form of linseed oil that has been modified so that, when water is mixed in, it doesn't separate. It is therefore possible to clean brushes in water rather than solvents, clean your palette with water, and so on. It is also possible to thin the paint with water, although manufacturers usually recommend against adding a whole lot of water. When mixed with water, the paint forms an emulsion (tiny droplets of water surrounded by oil), so the refraction index of the paint changes. That means that there is a noticeable shift in value; dark colors become a bit lighter. The paint returns to its normal value when the water evaporates away, making it difficult to judge values when painting (acrylic paint—another sort of emulsion—has the same problem). They take about as long to dry (oxidize) as regular oil paints. Water miscible oil paint can also be thinned with regular solvents, and manufacturers produce various mediums. They can even be mixed with regular oil paints, although no water should be added to such a mixture. Oil painters who try water miscible oils often find them to be kind of "sticky." Because each formulation is different, it can be a bad idea to mix paints from different brands. The big advantage to water miscible paint is that cleanup is easier and, well, cleanup is easier. Because the oil is real oil, I don't consider it unethical to label a painting made with water miscible oil paint as an "oil painting." So you don't have to try to educate buyers about a medium they’ve never heard of. Overall, though, I think water miscible paint is a solution in search of a problem.

Many people on internet art forums mistakenly refer to water miscible oil paint as "water soluble" oil paint: that’s not technically correct, any more than there is such a thing as water soluble olive oil. Many people who use the terms “water soluble” and “water miscible” as if they mean the same thing misspell "soluble" as "soluable." I hate that in the depths of my pedantic little soul. Remember: “soluble” does not have an “a” in it.Heat set “oil paints:” This is a line of paints marketed by one company: Genesis Artist Colors. I have not tried them. These are not actually oil paints, although the company describes them as “heat set artist oils” on their web site. The paints are instead ground in some sort of synthetic polymer that behaves rather like oil. It does not, however, dry by oxidation, the way oil paints do. In fact, it doesn't ever dry until you heat it to a high temperature, at which point it sets permanently. So you can leave paint on your brushes as long as you want. You don’t ever have to clean your palette—the paint stays wet forever. When you want a painting to be dry, you use a special heat gun (sold by the Genesis company) or a special drying oven (sold by the Genesis company). You can use a regular oven, but eventually, of course, you’re going to get paint on the inside of the oven. You can’t use a hair dryer because it doesn’t get hot enough. The big advantage of heat set paints is that you don’t have to worry about cleanup until you feel like it. When my son was born last week I left some oil paint on my palette: it’s now hard and will be a pain to scrape off. With heat set oils, that wouldn't be a problem. Some artists also like to noodle around with wet oil paint for days. Heat set paints don’t dry until you tell them to. The disadvantage to heat set paints is that they are made by only one company, and they won’t say exactly how they are made. They claim the paint is archival, but you have to take their word for it. Another disadvantage is that when you label one of these paintings, it would be a lie to say they are made with "oil paint." I'm not sure what you should call them—"heat set paint," maybe. I think its unethical for the company to call them “heat set artist oils,” because they are not oil paints, however much the finished product may look like an oil painting.

All of these paints are marketed to hobbyists, who like the idea of oil painting, but want something less inconvenient. Each of them corrects some perceived flaw in oil paints: they take too long to dry, they dry when you don’t want them to, you have to clean up with smelly stuff, and so on. These kinds of “improvements” mostly appeal to hobbyists who want their hobby to be more convenient. That isn’t to say that there aren’t professional artists who use each of these types of paint, or that wonderful paintings aren’t made with them. But any company hoping to make a profit selling what I will call “convenience oils” has to market them to hobbyists. That means they have to be fairly inexpensive, so the quality of most of these paints is about equivalent to student-grade oil paint. In order to keep the price low enough that hobbyists will buy it, alternative pigments, cheaper grades of pigment, and extenders are used, just as with student grade oil paint. Certain pigments that are more toxic, such as lead white and genuine vermillion, aren't manufactured in convenience lines of oil paint for the same reasons you don't find such pigments in student grade paint: most hobbyist painters are afraid of toxic chemicals they don't understand. It would be possible for companies to manufacture convenience oils with very high standards of quality, but that would be a bad business decision. (I am told that the water miscible paint made by Holbein is of fairly high quality, but I prefer not to use a type of paint made by only one company).

For that reason, I won’t use them. I like having access to the best grades of artist-quality oil paint. I like being able to use a wide range of traditional mediums that I can mix myself. I like having access to traditional pigments that have valuable properties but require particular care with regard to safety. And I like being part of a tradition of painting that goes back to the early Renaissance. While real oil paints can be inconvenient, none of the alternatives that have been developed are, to me, worth giving up the real thing.

Update 1: I'd like to note that water miscible oil paint can be useful if you want to travel by air with a set of oil paints. Because they are easier to use without solvents (which they won't let you travel with) water miscibles can be an alternative that is relatively hassle-free. If I were to do that, I would definitely buy the Holbein Duo Aqua oils, which I have heard good things about.

Update 2: One other characteristic of alkyd paints that I forgot to mention is this: alkyds need more binder to a given amount of pigment than oil paints do. That means paint manufacturers can't use as much pigment when making alkyd paints, so some colors don't have the saturation and intensity of their oil equivalents. That's not a failure on the part of manufacturers, but a characteristic of the alkyd medium.

Tags: painting, oil painting, painting materials

16 August 2006

12 August 2006

May be some time

In the meantime, I'd like to open comments to suggestions about any painting questions you feel confused about and would love to see a post (or series of posts) about. I may or may not be able to accomodate you (there's a heck of a lot about painting I'm clueless about). But if you post suggestions I'll try to come up with an answer. Just give me a bit of time before you complain that I haven't responded, OK?

Update: Brendan Connor Rourke was born at 6:08 PM on Monday, August 14th. He and the mother are both healthy. More later.

10 August 2006

"Turpentine"

That's confusing when you are trying to talk about artist's materials, however, because balsams such as Venice turpentine, Strasbourg turpentine, and Canada balsam are still in use. And, of course, spirits of turpentine are commonly used to thin paint. I try to use "spirits of turpentine" or "turps" to refer to the solvent.

Venice turpentine, by the way, isn't named after the city. It's a corruption of "vernice turpentine." "Vernice" is an old way of spelling "varnish." So Venice turpentine is a balsam that was commonly used in varnishes.

The Venice turpentine you can get in art stores is very expensive. It's also used in the care of horse's hooves, and you can get it much more cheaply from a tack shop.

Aren't I full of marginally useful information?

Studio safety and oil painting

First, the oil in oil paint is natural and non-toxic. I've seen people on internet forums say that they are switching to acrylic because they're concerned about the toxicity of oils. That's funny, because oil is less toxic than the acrylic polymer emulsion used to bind acrylic paint. All of the different kinds of oils (linseed, walnut, poppyseed, safflower) can be found in health food stores (linseed oil is also called flax seed oil). They are edible and have a pleasant, mild odor.

Pigments are, with a few exceptions, the same from one kind of paint to another. Some of them are mildly or moderately hazardous to ingest and some of them are, basically, dirt. Cadmium colors are used in most varieties of paint, including acrylic and watercolor—they're very bad to eat. You can, if you choose, get a few pigments in oil that are particularly bad to ingest, but you have to seek those out. They include flake white, genuine vermillion, genuine Naples yellow, and lead tin yellow. However, the same resonable precautions that you should use with other paints—which I'll describe shortly—will also keep you safe if you choose to use these specialty pigments. There are also some paint additives, such as cobalt drier, black oil, Maroger's medium, and lead napthenate, that contain substances that are hazardous to consume.

I'd like to particularly mention lead, because some artists may be confused by what they see on the local TV news. The problems that arise with leaded interior house paint are not relevant to making art unless you plan to let children eat your paintings (I would strongly recommend against this). Lead is hazardous if it enters your bloodstream, but if you are careful, that’s very unlikely. It doesn’t penetrate skin. It won’t hurt you unless you eat it, breathe lead powder, rub it in your eyes, or fail to duck if someone tries to shoot you with lead bullets. Paint containing lead doesn't give off toxic fumes. Although it may be wise to avoid powdered lead pigment (as well as other hazardous pigments in powder form), prepared materials containing lead can be quite useful.

I do recommend that pregnant and nursing women have nothing to do with materials containing lead, cadmium, or mercury. That doesn't mean there is any reason to give up oil painting, just that you should avoid certain pigments.

The colorless pigments added to oil paint as extenders, such as alumina stearate or blanc fixe, are not something I'd put on my breakfast cereal, but neither are they particularly toxic. Nor are the resins or waxes a few companies include in their paint formulations.

No matter what pigments you work with, you need to make sure that you don't ingest paint. That means that you must develop safe and consistent work habits. Never put brushes in your mouth. Never touch your face or hair while painting. Don't eat, drink, or smoke while painting. Use disposable gloves if you have cuts on your hands. Make sure your workspace has good ventilation. Wash your hands (including under your fingernails) and all of your tools thoroughly after painting. Clean up your work area when you are done. And always make sure that painting materials are inaccessible to children and pets.

Solvents such as spirits of turpentine, mineral spirits, denatured alcohol, and oil of spike should be used with some care. Because they are volatile and evaporate quickly, use them in areas with good ventilation. They are potentially flammable, so don't allow open flames where solvents are being used. Some people are very sensitive to the smell of spirits of turpentine. Good quality artist's turps (I like the stuff from Winsor-Newton) are more expensive, but smell a lot better than the awful stuff you get in hardware stores. Keep any container with solvents covered when not in use—don't have jars of medium or brush washing solvent just sitting open when you paint. Instead, keep the jar closed when you're not using it and don't leave brushes sitting in solvent—it's not good for them anyway. Mineral spirits and other odorless thinners don't have a noticeable smell, but don't be careless with those, either. They can cause headaches (which you might not ascribe to a substance without a smell) and some people (including me) have skin sensitivities to them.

If you are sensitive to solvents, it is possible to use oil paint without them. You can buy a jug of cheap linseed oil and clean up with that. You can use it to wipe your brushes as well (wash with soap and water afterward). You can avoid thinning your paint, or just add a touch of oil.

One rare but potentially severe hazard with oil painting is spontaneous combustion. Drying oils, under rare circumstances, can generate enough heat when drying (oxidizing) to catch on fire. That's not a concern on the surface of a painting or in a closed container, but in a closed space that allows oxygen to enter, such as a trash bin, a pile of rags or paper towels soaked in oil or oil paint can combust. It is best to either have a fire retardent trash can, or throw rags into a container half full of water. I sometimes allow painting rags to collect in in the open on a counter. When it's time to throw them away I put them into a plastic grocery bag, soak them in water, and put them into the trash for pickup the next day.

If you are one of those rare artists who makes their own paint by working with powdered pigments, then always use a dust mask, even with pigments that are only powdered earths. You only ever get one set of lungs.

I think that's it. Use reasonable and sensible precautions, and don't worry.

09 August 2006

Eiffel flashing

This is the Eiffel Tower, seen at night from the first of three stages in the journey to the top. Every fifteen minutes (I think) there is a small light show across tower, and I managed to catch this shot with the lights going.

This is the Eiffel Tower, seen at night from the first of three stages in the journey to the top. Every fifteen minutes (I think) there is a small light show across tower, and I managed to catch this shot with the lights going.This photo had a lot of digital noise. To correct this in Photoshop, I copied the image to a new layer, set the blending mode to Color, and applied a gaussian blur. This removed the noise without removing detail.

08 August 2006

Making gesso, part 2

Making gesso

Measure the volume of the remaining glue and pour it back into the double boiler. You will be adding 1.5 times this volume of chalk or gypsum to make gesso. Do this gradually, gently dropping each spoonful into the liquid to avoid making any bubbles. Distribute the chalk/gypsum around the pan so that it the glue soaks into it. Once all of the chalk/gypsum is in the pot, give it 10 minutes to soak. Now take a brush and gently stir the mixture, again trying to avoid making any bubbles.

Applying gesso

For the first layer, spread it thinly over the surface of the panel, stroking back and forth in one direction. It's not very opaque when wet. Let it dry' this takes 10-30 minutes, depending on humidity and temperature (dry days are best for gessoing panels). You'll know it's dry when it feels dry to the touch and any grayish areas have disappeared.

If the gesso is getting thick, it means that it's cooling off. Replace the water in the double boiler with new hot tapwater.

You will apply 6-8 layers of gesso. Brushstrokes in each layer should be applied at right angles to those of the previous layer. Each layer is best applied shortly after the previous layer has become dry. It's best to apply all layers in one day, so that they will bond with each other. If you get cracking, that means that you're applying the gesso before the previous layer has dried. More layers will fix this. If you get little pits in the gesso, then you're painting with gesso that has bubbles in it. Let the gesso stand for a half hour before applying any more, then rub the next layer in with your hand.

Once you've applied all the gesso, let the panel dry for at least three days. You can clean the brush, pan, and anything else that got gesso on it in warm water.

Smoothing the panel

Start by using a metal file to chamfer all of the edges of the gesso, so that they are at a beveled angle inward. This protects against cracking, should the panel strike something (I've had this happen, and it's very irritating).

To get the panel smooth, I like to use a sanding block, starting with 400 grit sandpaper and moving to finer grits at the end. This produces a beautiful, eggshell-smooth finish that is almost too beautiful to paint on.

If I'm going to be painting with oil, I like to apply a final layer of hide glue to the smoothed surface of the panel. Without that, the gesso is a bit too absorbent. For egg tempera or tempera grassa, plain gesso works great.

07 August 2006

Oil on copper

I've never painted on copper, but I've wanted to for a long time. Copper is, historically, one of the most stable supports to paint on with oil. I recently purchased some small 5 x 7" sheets of copper from the hardware store. I mounted this one on hardboard with Gorilla Glue. I then cleaned it with denatured alcohol and scuffed it with sandpaper. While painters back in the day primed with lead white, I'm going to paint directly on the surface of the copper and leave some of it showing. The panel looks beautiful and I really want to see how it takes the paint. I'll let you know how it turns out.

I've never painted on copper, but I've wanted to for a long time. Copper is, historically, one of the most stable supports to paint on with oil. I recently purchased some small 5 x 7" sheets of copper from the hardware store. I mounted this one on hardboard with Gorilla Glue. I then cleaned it with denatured alcohol and scuffed it with sandpaper. While painters back in the day primed with lead white, I'm going to paint directly on the surface of the copper and leave some of it showing. The panel looks beautiful and I really want to see how it takes the paint. I'll let you know how it turns out.

06 August 2006

Making gesso, part 1

Gessoing is easy and almost foolproof, but time-consuming. It takes an afternoon to gesso a panel. On the other hand, it takes an afternoon to gesso five, ten, or twenty panels, so it pays to produce them in volume. I generally invest three or four afternoons a year in making enough panels to provide me with a steady supply.

Here's how to make and apply gesso:

Materials

Hide glue (often labeled "rabbitskin glue" whether it contains any rabbit or not). Most major art suppliers have this.

Inert white pigment. This is powdered chalk or gypsum. The marble dust you can buy in art stores is chalk. Plaster of Paris is cooked (anhydrous) gypsum, but I have found it too gritty to make good gesso. (The word "gesso" means "gypsum" in Italian, since that's what Italians made gesso from. In Northern Europe, chalk was the traditional material). You can buy good-quality powdered gypsum from specialty suppliers like Kremer.

Titanium white pigment. This is optional. Some people like to substitute up to 20% of the intert white pigment in the recipe below with titanium white, for brightness. I haven't found it worth the bother.

Panel. There are various materials you can use for panel painting. One good option is to buy hardboard at the home improvement or hardware store. You can buy it cheaply in 4 foot by 8 foot sheets. Get tempered hardboard 1/4 inch thick. The staff at the store will probably cut it to size for you if you ask. Other materials you can use for panel include medium density fiberboard (MDF) and actual wood planks. Wood panels of any size, however, is best seasoned for 1-3 years, with planing to size if it warps, after it has been cut.

Wide flat brush. A good housepainting brush will do.

A double boiler. Or use one pan that can fit inside a larger pan.

Measuring spoons, mixing spoons.

Sandpaper. Several grits.

Preparing hide glue

Make the hide glue the day before you plan to gesso the panel. Hide glue normally comes in powder or granular form. Mix one part hide glue with 11 parts warm tap water. One cup makes about enough to size and gesso two 8 x 10" panels, depending on how many layers of gesso you apply. Stir the water/glue mixture for about five minutes, then let it sit for 6-24 hours or so. It will form a thick gelatin. If the weather is very hot (95 degrees farenheight+), it might not gel properly unless you put it in the refrigerator.

Preparing and sizing the panel

The edges of the panel should be smoothed with sandpaper or a rasp. Clean the panel with denatured alcohol to remove any trace of oil or other guck.

Now you want to coat the panel in a layer of hide glue. This is called sizing the panel because another word for hide glue is "size." You'll start by warming the glue to make it fluid. If you heat the glue too much, it will weaken the glue. As it turns out, hot tap water is about the right temperature to liquefy glue without damaging it. So fill the outer pan of your double boiler and put the glue into the inner pan. In about ten minutes, it will be about the consistency of milk (whole milk, not that low fat stuff). Brush the glue over the front, back, and sides of the panel. Give it a half hour to dry.

I generally add more layers of glue to the back. The reason is that the glue in the gesso on the front will be applying force to the panel. If the panel is large, this will noticeably warp the panel. So I generally add about four layers of glue to the back in order to counteract the warping effect that the gesso will apply to the front. This seems to help a lot.

05 August 2006

Studio Products

Here are a few of the products from their catalog that I've tried.

Lead primer in black oil: this is a perfect lead white primer. It doesn't dry to a brilliant white, but rather to a pleasant warm tone.

Black oil: This is linseed oil cooked with lead. Black oil is slippery and dries very quickly; it is an excellent component in painting mediums.

Glazing medium: Use this by spreading a thin layer onto the dried surface of your painting, then applying paint thinly into it. Thick and slippery.

Special aged oil: This is a particular grade of linseed oil, excellent for grinding your own paint and for making egg-oil emulsions.

Oil paint: as I said, I have not encountered anything better. It has the kind of consistency you get with freshly ground, homemade oil paint. It is expensive, but note that their standard tube is 50 ml while most of their competitors use 40 ml tubes, so it's not quite as costly as it looks.

Oil of spike: This is a solvent, similar to spirits of turpentine. Compared to turps, it evaporates more slowly and is more slippery. It has a strong, pleasant smell.

Maroger's medium: This is black oil and thick mastic varnish. You can buy a pre-made version or one that you mix up yourself (it takes 20 minutes to gel). Added in very small quantities to paint, Maroger's noticeably improves the handling quality of oil paint.

The company also hosts the Cennini Forum, a place where painting topics are discussed with a knowledgeable and lively group of artists. The moderator is Rob Howard, whose sometimes acerbic style of forum management does not agree with everyone. If you stick around, you'll learn lots about painting and painting materials.

Wet sanding

Once the paint has dried thoroughly, it is sometimes advantageous to sand the surface down slightly. In order sand very smoothly, and in order to avoid breathing pigment dust, it is best to use a wet sanding technique. Lay the painting down on a flat surface. Spray some water on the surface, or wipe it down with a wet cloth (adding a few drops of dish detergent is helpful for lubrication). Now use a wet green kitchen scrubee pad to gently sand the surface. Unless you want to remove some mistake, the idea is to lightly rub the pad around, without applying significant downward pressure. Some paint will come up and the water will change color; that's OK. Do this over the whole surface until it feels smooth. Now, before any evaporation occurs, wipe all of the dirty water off of the surface with a paper towel. That way, you don't have to worry about pigment dust. Let the painting dry before painting on it again; often an additional day is a good idea to allow any tacky paint revealed by sanding to dry out.

Wet sanding removes unwanted impasto, removes surface gloss and creates a uniform satin texture, and produces a surface that is easy for the next layer of paint to adhere to. It's often a good idea for indirect painting. Wet sanding creates an inviting surface that really feels good to paint on.

04 August 2006

Student grade paint

If you are just starting to learn oil painting, don't buy the student grade paint. It's hard enough to learn how to work with good oil paint, let alone handicapping yourself with the cheap stuff. Student grade paint doesn't handle very well and the substitute pigments are of much lower quality. Because they use extenders and fillers, the paint doesn't go as far.

If you don't have a lot of money, buy fewer different colors of good quality paint. Get earth colors, ultramarine, and other pigments that are inexpensive. You can do a lot with just five or six tubes of paint. Add more colors as you can afford them.

Robert Doak makes very high quality paint that is quite affordable, by the way.

03 August 2006

Comment spam

I'd rather not have to manually delete comment spam. I could (1) turn on comment moderation, so that comments don't appear until I approve them; or (2) turn on comment verification, so that someone who wants to post a comment needs to type in a string of numbers and letters in order to post a comment. Both of these options are annoying.

Anyone have an opinion?

Update 8/5/06: I've enabled comment moderation.

Update: 8/7/06: I was wondering how long it would take for this post to get comment spam. Four days.

Work in progress

Here's where it's at a day later. Because I used flake white for the background yesterday, it is touch dry and can be painted upon without any tackiness (oil painting with flake white is a noticeably different experience than using any other white).

Here's where it's at a day later. Because I used flake white for the background yesterday, it is touch dry and can be painted upon without any tackiness (oil painting with flake white is a noticeably different experience than using any other white).I'm now working up the foreground, developing the boot on the left. For the most part, I'm attempting to finish each section completely and move on to the next, rather than follow the more common oil painting strategy of painting in big shapes throughout and then refining in later stages (not that I won't go back and fix something if needed). I can see now that a few of the lines and curves need to be slightly adjusted for perspective.

As I noted earlier, I'm not using black. The base color consists of a mixture of pyrol ruby and viridian, lightened with flake white and toned with varying amounts of ultramarine blue, burnt umber, and burnt sienna.

02 August 2006

Work in progress

I started this today while waiting for a couple of other pieces to dry (slow drying is the joy and the curse of oil painting). It's similar to my earlier painting of blue jeans, in that it's stuff hung on my wall in strong raking light. If I keep this up, I'll have a series.

I started this today while waiting for a couple of other pieces to dry (slow drying is the joy and the curse of oil painting). It's similar to my earlier painting of blue jeans, in that it's stuff hung on my wall in strong raking light. If I keep this up, I'll have a series.This is 12 x 16", oil on 1/4" lead primed hardboard panel. I sketched in the basic forms with burnt umber mixed with ultramarine blue (thinned a bit with turps and a touch of linseed oil), then laid in a first layer for the background and main shadows with various combinations of flake white, burnt umber, raw sienna, and Doak's wonderful Alger blue (a variation on cobalt blue). Next I'll start to work up the general forms of the boots. My plan is to do this without black. (Not because I'm one of those "I never use black" kinds of artists, but because that much black would be deadening. Plus, it'll be a fun challenge.)

Real gesso

Actual gesso has been used since the Middle Ages as a ground for painting. It's made from hide glue and an inert white pigment such as chalk or gypsum (it may also have a stronger white pigment such as titanium white added for brightness). Traditional gesso is a good alternative to acrylic primer if you are painting on panels (it's too brittle for use on canvas). You can make it yourself, but if you'd rather not go through the trouble, the best commercial gesso panels I know of are made by these guys:

http://www.realgesso.com

Their panels are excellent for oil, egg tempera, or tempera grassa. They are made with 1/4" tempered hardboard spray-coated with gesso made from hide glue, powdered chalk, and titanium white. A 16 x 20" panel currently costs $20.80 USD, which is quite reasonable. They sell a variety of sizes and will custom cut for no additional fee. Smaller "plein air" panels on thinner hardboard are also available, as well as oil-primed linen glued to hardboard.

They will send you a sample for free if you ask. If you've been painting on generic primed canvas or making your own supports with acrylic primer, this is a real step up.

In a later post, I'll provide instructions for making your own gesso panels.

01 August 2006

Pthalo pigments

The reason is that they are too bloody strong. Pthalo blue is something like 40 times as strong a tinter as ultramarine blue. That means, for example, that in order to change the color of titanium white by 10%, you would add 40 times as much ultramarine blue as pthalo blue. That sounds like a good thing (efficient!), but in fact it's infuriating. In mixing, it is extraordinarily difficult to add a small enough amount of a pthalo color to get the effect you're looking for. Paint manufacturers reduce this problem somewhat by adding colorless extenders to some pthalo paints, but that only goes so far. Some artists learn to manage with pthalos (they are, in fact, quite popular artist's colors), but I hate trying to work with infinitesimal amounts of paint when trying to make subtle changes to mixtures, so they drive me nuts.

Fortunately, there are good substitutes. Prussian blue is almost exactly the same hue and transparency as a neutral (not green or violet) shade of pthalo blue, but a lot less strong. And viridian is very similar to a neutral pthalo green. So if you have trouble mixing with pthalo colors, try those instead.